If someone brings up Costa Rica, a few things may come to mind. Surfing, ziplining, jungles, perhaps a toucan or a sloth. Our drive down the Transamerican Highway reflected that: bright adventure-advertising billboards in English popped out from all sides. This is the touristy piece of the country. I expected this: we were on a guided tour and hoped to visit some of the more popular places in Costa Rica. We wished to see owls, so we were headed to a place called the Nest Nature Center, in search of the elusive Striped Owl. Our guide told us the Striped Owl was not a guaranteed bird, birds can fly and leave properties. Meanwhile, I heard ‘nature center’ and pictured a garden-style place with a visitor center. It wasn’t until we pulled off the highway and into the quiet, working-class community of Monte Cristo that I realized we were headed off the beaten path. Based on the looks residents gave our white, TURISMO stickered van, this town definitely didn’t have a lot of gift shops. We kept driving and pulled up a steep alley, which looked like any other alley, bordered by houses and fences. A few more seconds and we entered a jungle. Not a jungle of power lines or discarded furniture, we found ourselves in a piece of wild Costa Rica in sight of the road. This is the Nest Nature Center.

Located in northern Costa Rica, the Nest Nature Center is a pasture-turned avian paradise. Like many places around the globe, the Nest was created to restore land damaged by cattle farming and other monocultures. In Costa Rica, cattle farming is extremely problematic for conservation efforts, as massive sections of vegetation are cleared away on the cow’s behalf. Recognizing the importance of a healthy ecosystem and what little money his family was making off of the property, Juan Deigo-Vargas bought what is now the Nest and cleared away the cows. The first step was repopulating the property with trees. Once his forest began to grow, Juan added small bodies of water and planted flowers for hummingbirds. The final step was building feeders and a balcony to view birds from. Juan’s project started over 30 years ago and centers around ecotourism and preserving biodiversity.

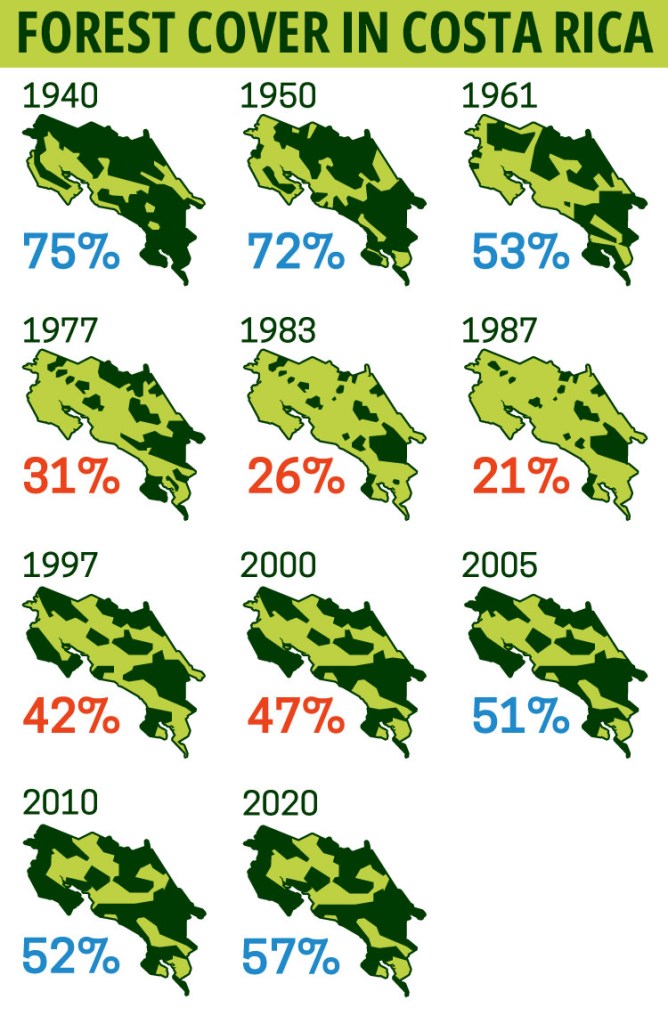

Bordered by oceans on either side, Nicaragua to the north and Panama to the south, Costa Rica is on the smaller side, slightly smaller than Lake Michigan. Yet the Central American country is one of the most biodiverse in the world. One of the reasons is Costa Rica’s lush, tropical forests. In the mid-20th century, roughly three quarters of the country was forested. However, that number dropped to less than a quarter by 1987. How? The enemy of all forests: deforestation. Whether in the name of logging, or the expansion of agricultural properties, deforestation has been consuming the world’s forests for centuries. How then, if Costa Rica was losing its forests at such a dramatic rate, is there any left for us to enjoy? The answer: conservation and dedication. In 1996, the Costa Rican government banned logging and a year later, introduced a program which paid landowners to practice conservation on their properties. Over the past half century, Costa Rican forests have made a dramatic comeback and now over half the country is forested. Even though trees are still cleared in the name of agriculture, deforestation is taking a much smaller toll on the country, thanks to protected areas and dedicated conservationists like those at the Nest.

The Nest is what we call a biological island, which means it is a piece of the ecosystem – often protected from deforestation and monocultures – but not connected to any other protected areas. For instance, the Nest was originally a farm on the outskirts of town and surrounded by other farms. Now, it is a biological preserve on the outskirts of town and surrounded by farms. Because there is nothing connecting the Nest to any other protected area, the Nest is a biological island. When two islands are connected, they form a biological corridor, which increases the amount of protected nature and allows the animals inhabiting the former islands to travel safely between them. Biological islands and corridors are crucial to maintaining an area’s ecosystem and biodiversity, one of the reasons the Nest is such an important piece of nature.

Since Juan’s project began, he has counted over 200 species of birds, many of which now call the jungle island home. Some of the Nest’s avifauna are still knee-deep in trouble, as prime nesting and living locations vanish. Without the Nest and other biological islands, many bird species would be a lot worse off than they are right now. A perfect example of a bird who has returned thanks to the Nest’s conservation efforts is the Striped Owl. To be clear, Juan never meant for the Striped Owl to nest on his property. In fact, he wanted the whole property to be forested, something the cattle previously living on the property prevented. The cattle preferred a certain corner of the property, leading to the complete destruction of the soil in that spot. Because their grazing impacted the corner’s soil in such a harmful way, the large, rainforest trees Juan hoped for could not grow there. Instead, a few deciduous bushes and the tall grass Striped Owls needed were all that sprouted in that corner. We were lucky enough to get a glimpse of the elusive species during our visit to the Nest, but only with the help of someone who was experienced in finding it! Striped Owls are fascinating birds because of their nesting habits: each year they build a nest on the ground and lay 2-3 white eggs. Although they nest on the ground, deforestation still impacts them since the male needs trees to keep watch from. The long grass necessary to hide their nest from potential predators is cut down to make pasture and – in the case of plantations – removed entirely to create space for pineapples, watermelon, sugarcane, and palm oil. Now, imagine how much of a difference a place like the Nest makes for species such as the Striped Owl. Even though a single pair lives at the Nest, each year more baby Striped Owls are reared and sent off into the world. So, you can see why places like the Nest Nature Center are so crucial in the avian world, especially with the challenges, both human and natural, each species faces.

The Nest is an amazing example of fighting back against deforestation, and you can help – even in your own backyard! You have probably heard lawns are biologically deserts, and that is one hundred percent true. Kentucky Bluegrass is the largest monoculture in the United States. Every piece of lawn covered in this grass is a piece which used to be covered in native flora. Additionally, imagine every drop of pesticide and fertilizer people put into their yards every year. That being said, the United States is doing a much worse job conservation-wise than Costa Rica. We lose millions of acres of forests each year. Fortunately, rewilding programs are springing up across the country and lots of yards are experiencing an introduction of native flora. By dedicating small chunks of your property for rewilding purposes, your yard will turn from a desert to an oasis.

I hope the Nest Nature Center inspires you to stand up against deforestation and monocultures. If you don’t have the time, space, or money to remodel your yard, consider checking out the Nest’s website and support their mission. Links to the Nest’s main website and Nest related things are below.

The Nest Nature Center Main Website

- Booking day trips, overnight stays, and local birding

- About them

- Contact info

Upcoming Virtual Tour of the Nest

Through Eventbrite + Indiana Audubon + Lifer Nature Tours + Zoom

February 7th, 2026

8:00 am Central

1 hour long

15-20 in USD (US Dollars)

Great post Dottie! I love all the information you provided about the problems of deforestation and how it impacts birds in Costa Rica. I also liked the ways we can make a difference by creating our own NEST in our communities or backyards.

LikeLike